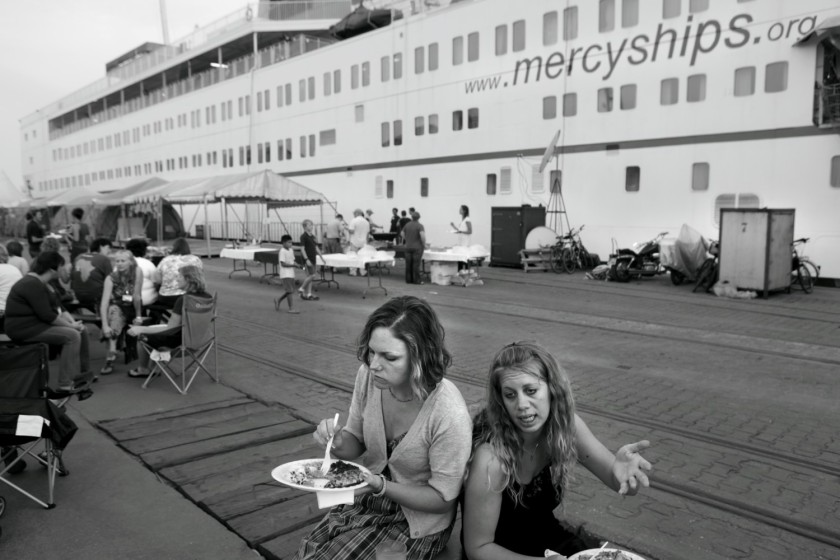

In June I posted about Ayabavi, one of the terminally ill cancer patients that Mercy Ships was looking after. In August myself and Claire visited her along with Harriet and Alex on their last visit. The two weeks previous I also tagged along with the palliative care team visiting two other patients; Lucie and Eklou. The following are very briefs accounts of the effects that the cancer and Mercy Ships has had on their lives, followed by a series of portraits and stills showing where and how they live.

Lucie Amedji

When she first noticed the lump in March earlier this year she felt fine, she was selling second hand clothes on the roadside. It soon got very painful, and she realised her sight was diminishing. As it grew larger her sight went completely. The doctor gave her some eyedrops, but didn’t even mention removing it. She carried on working.

On a visit to Aneho to pick up more of the eyedrops they had another look and told her they couldn’t do anything, sending her to the general hospital in Lomé. They informed her they could do surgery, but the cost was far more than she could afford.

Lucie lives at the Auberge du Lac, a backpackers on the beach of Lake Togo, owned by her Uncle who lives in Germany. He came back to see her and got in touch with Mercy Ships, arranging for her to go to one of their screenings.

She learned about the cancerous nature of the tumour from the doctor on board the ship.

Each week Harriet and Alex bring her painkillers, bandage dressings and fruit. They counsel her, and try to help her cope with her short future. I’ve mentioned before that they often read through the bible with their patients, suggesting areas that may provide comfort. The three patients I’ve photographed in this post are all Christian, and all expressed to me their appreciation for the palliative care team for reading through the bible with them and the prayers they share.

Lucie gets visits from her pastor and members of her church each week. She is grateful for the moral support and friendship they’ve shown. The pain relief the drugs have provided have made an enormous difference in her life. It is this that concerns her most about the Africa Mercy’s Togo field service ending. Without them she is in constant agony, totally immobile and would surely not live long. While she can carry on taking them she has been able to resume her job selling clothes. Without the pain she has been out and about more of recent, and has a certain joy she hasn’t felt in a while.

The supply of drugs that the palliative care team provides will run out a couple of months after their last visit (which was the beginning of August). The cocktail of painkillers she requires costs in the region of $60 a month. Her church community cannot help her financially. She earns an average of about $1 a day.

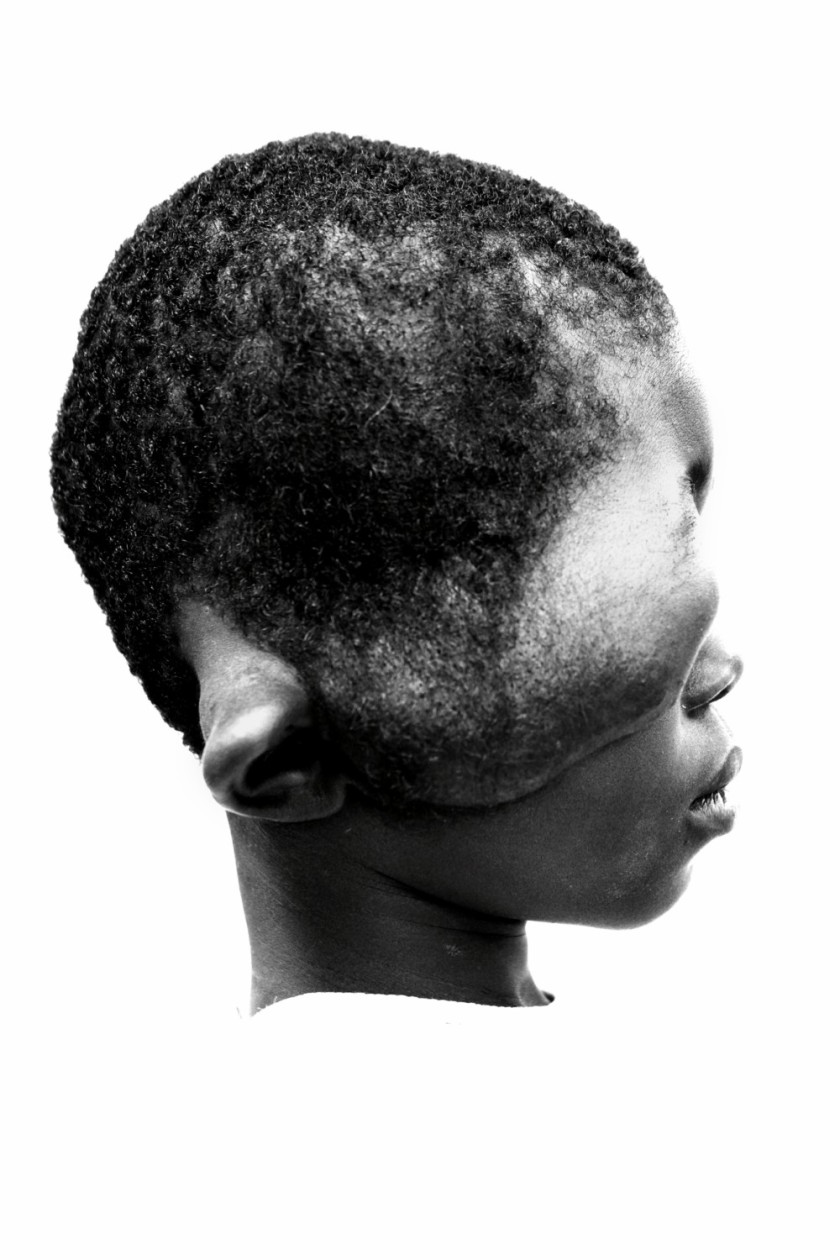

Lucie.

Lucie and her father.

Looking through Lucie’s front door.

Lucie’s house.

Lucie talks to her cousin.

Lucie and her niece.

Lucie waits for her father.

Electricity cables above the TV.

A bar stool keeps the tap closed.

Fisherman fold their netting after their morning catch outside Lucie’s house.

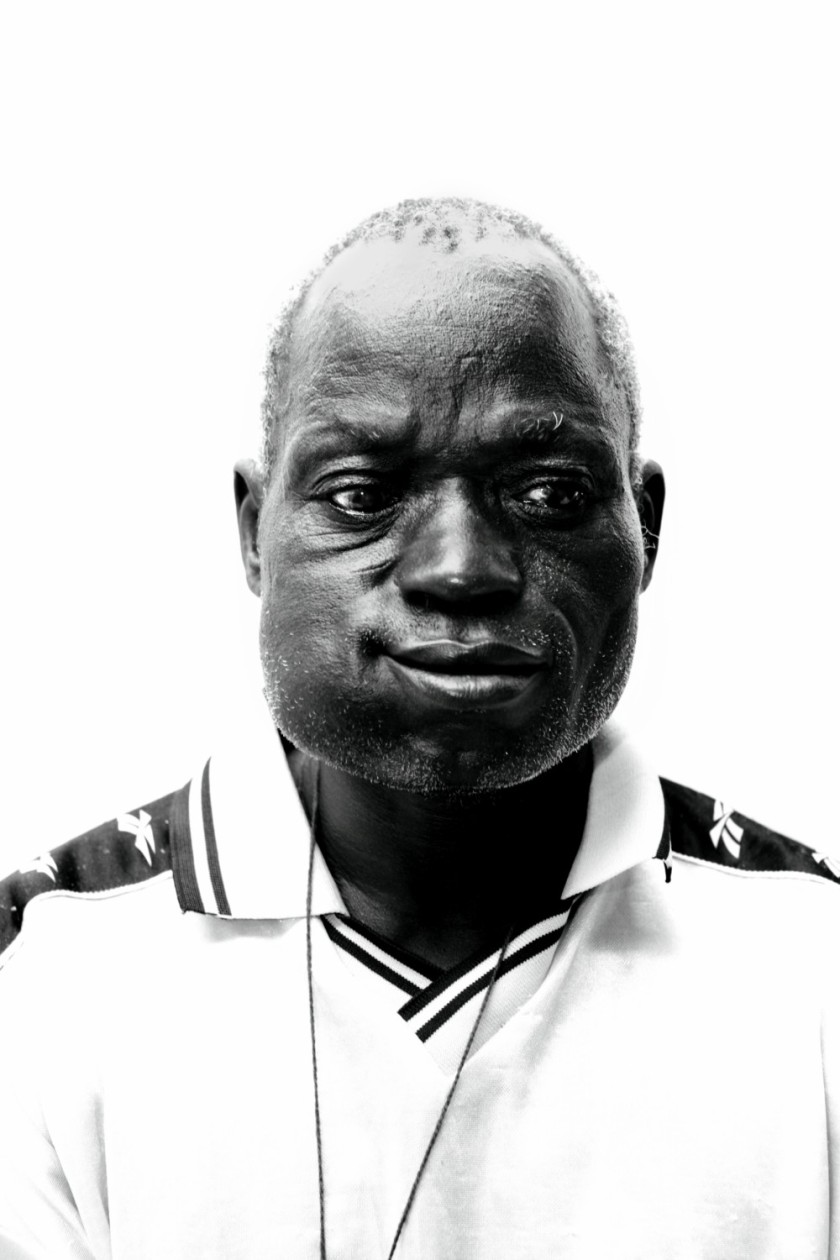

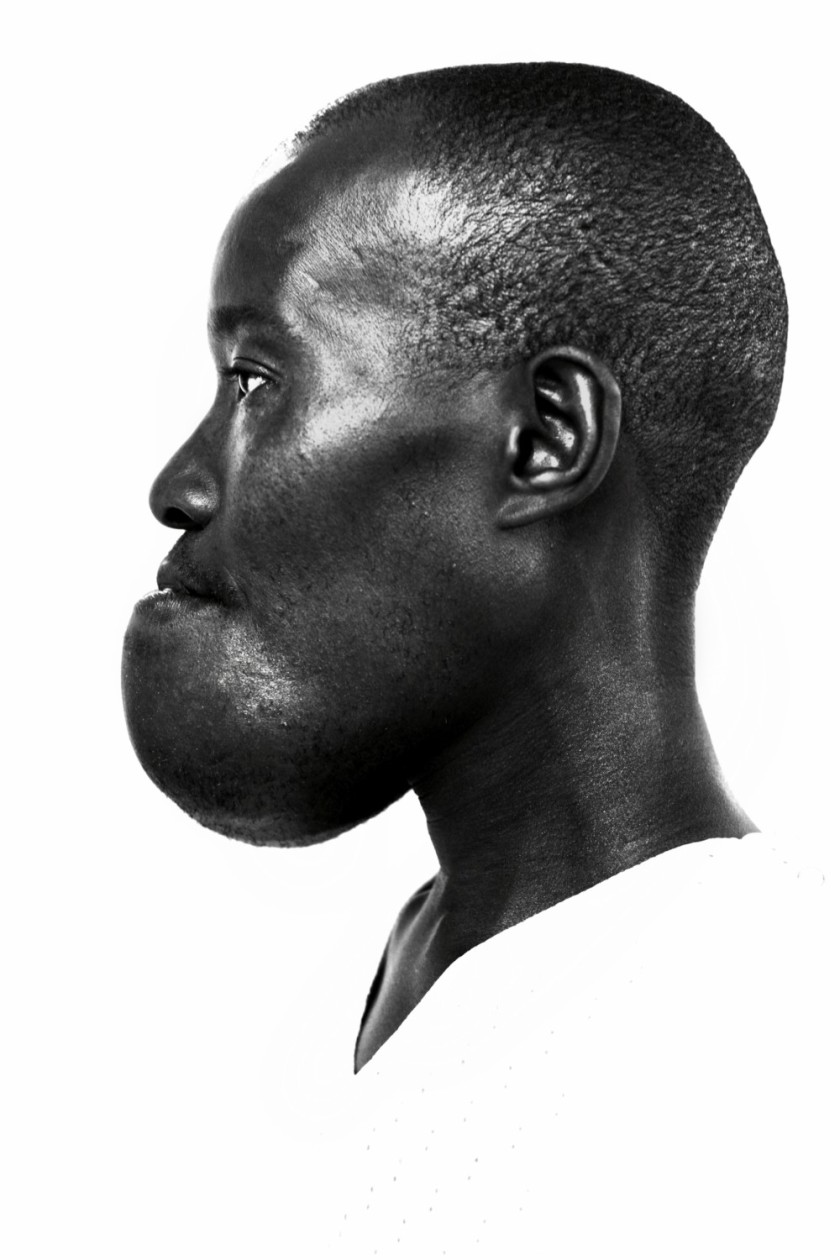

Eklou Gnakou

He’s had a tumour on the right side of his face for many years now. It’s been operated on twice, both times by Dr. Amaglo, a local surgeon that has worked on the Africa Mercy before.

He owns a plot of land which he used to farm and sell the produce. He carried on working after the first operation, but after the tumour grew back and was removed a second time he was too weak, and had to stop farming.

He heard about Mercy Ships and went to a screening where he was told that he couldn’t be operated on again – it was malignant. He still asked to be operated on even then, but after talking with Harriet he understood, and realised it was futile.

He is extremely grateful to Mercy Ships for a number of obvious reasons, but partly because he would have paid for a third operation which he now knows wouldn’t have got rid of the cancer. He’d like to take the hospital he was operated on to court, partly because they should have told him the operation wasn’t enough, partly because they waited a year before he got the results of the operation.

Money has been an issue for him since he stopped working on his plot of land. He has seven children, four of which live at home. At the moment he is able to feed them all and send them to school, but his eldest son Kofa, 14 works constantly in their garden to make sure food is growing. Kofa tries not to think about his father’s illness. He says that he feels sad when he does, and he doesn’t want to think about who might provide for the family after his Dad has gone. At the moment he can see that his father’s in much less pain than he used to be, and they’re managing at the present.

Though Eklou is more able to work with the drugs that the palliative care team provides, he does not have the money to start up the plot of land he farmed on before. He owns it still, but cannot afford to use it. He needs help from a microfinance organisation, but because of his cancer will almost certainly get turned down.

In an understandable attempt to get rid of the cancer a rich Uncle is paying for him to have radiotherapy in Ghana. Radiotherapy usually shrinks the tumour quite quickly, but if there’s any trace left it will grow back rapidly. There is little chance that the radiotherapy will work, but Eklou is hopeful. – the doctors there have told him that after treatment his cancer will be gone forever.

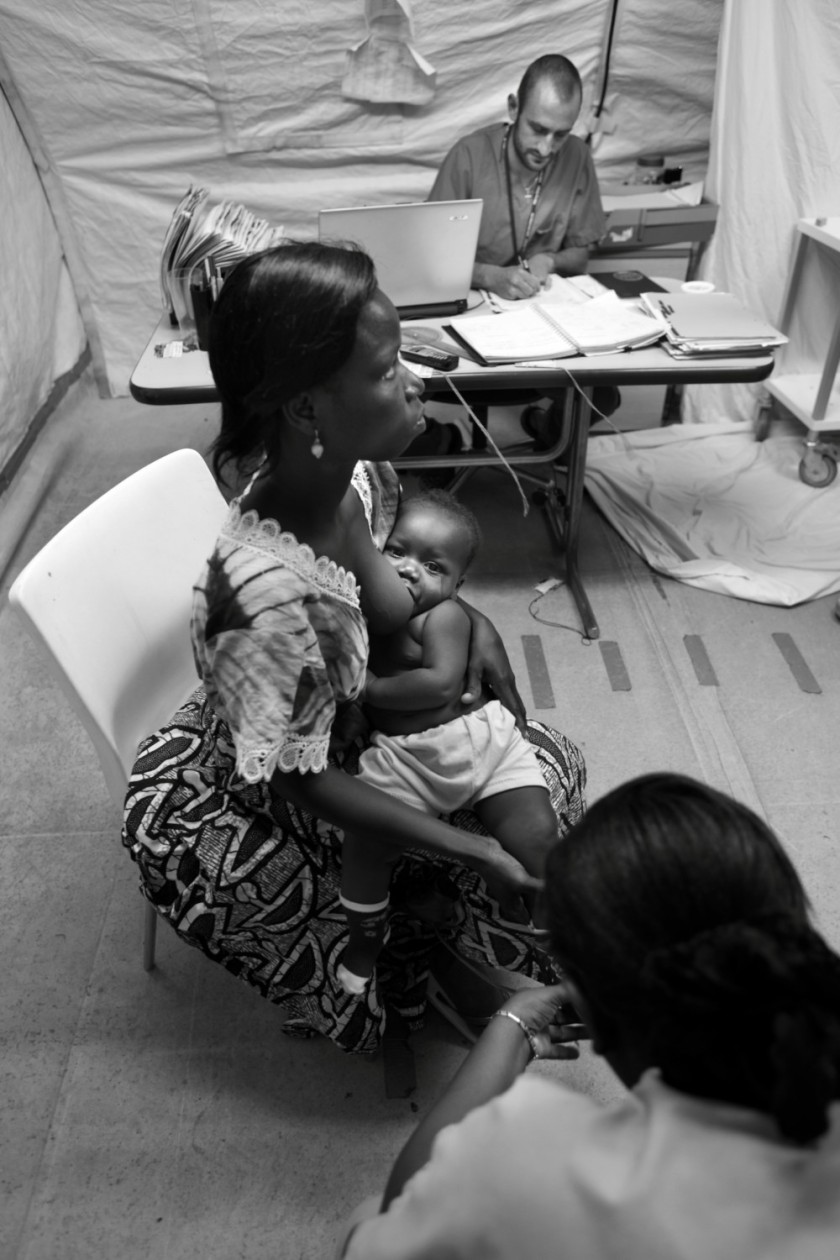

Eklou talks to the palliative care team.

Eklou’s children leave their toys in the yard.

Eklou explains his concerns for his families welfare after he’s gone.

Alex listens with concern.

Eklou with some of his children.

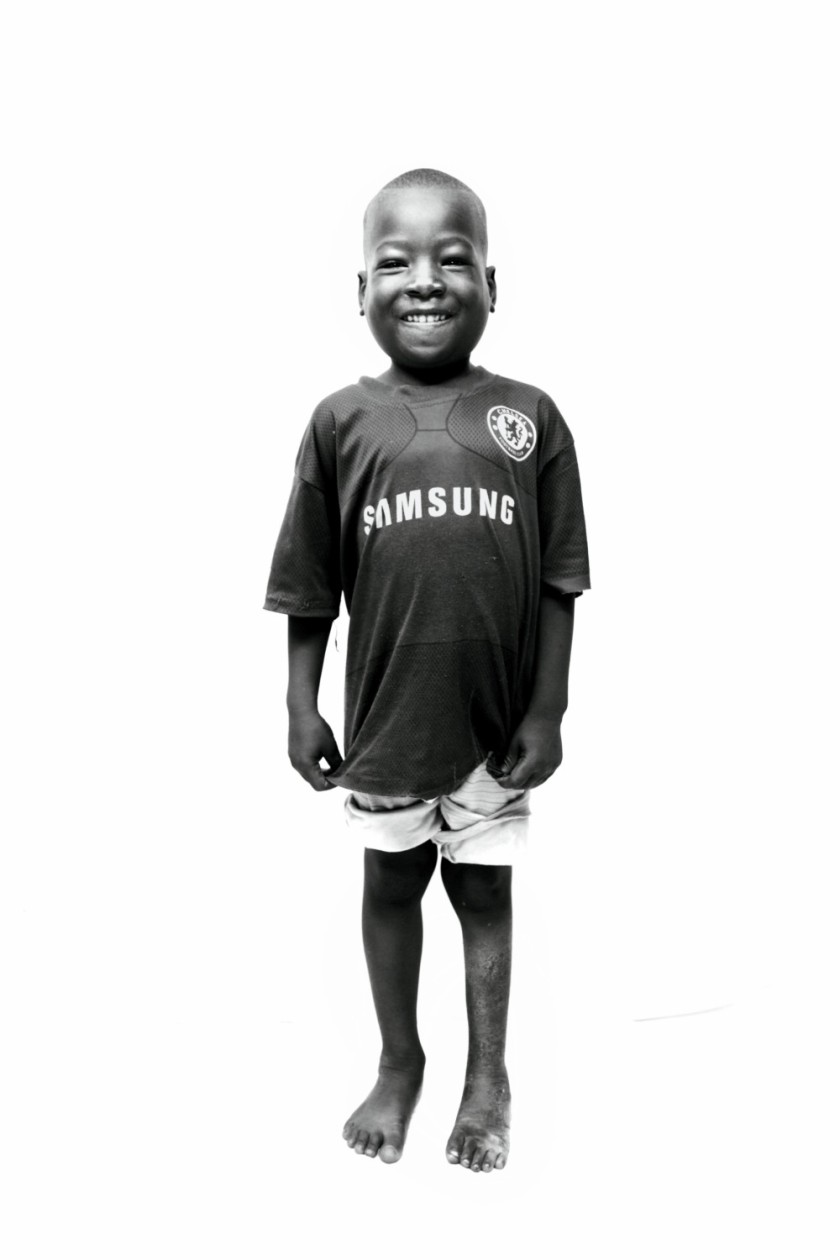

Kofa and his younger sister.

Harriet’s medical kit.

A blackboard that Eklou’s children use at home.

A stopped clock in Eklou’s bedroom. Despite being Christian, his wife is obsessed with voodoo.

The patch of land in Eklou’s yard that he and his son Kofa maintain.

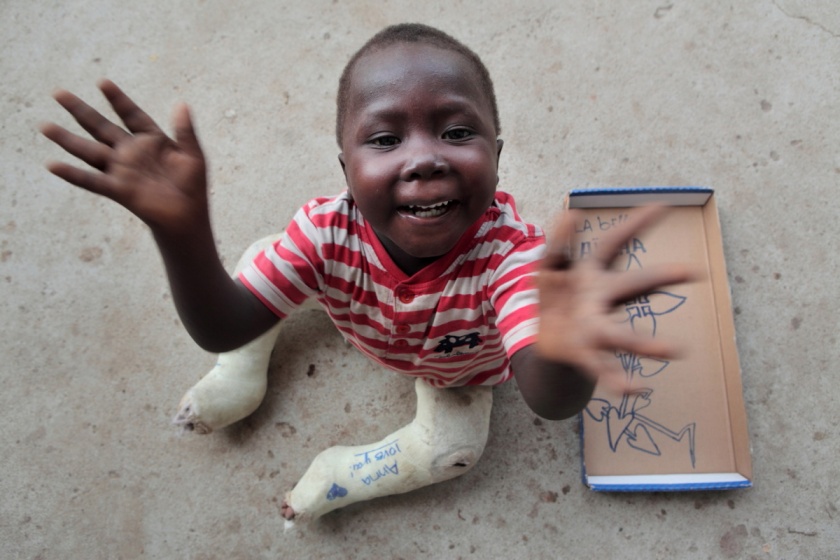

Ayabavi Fiodegbekou

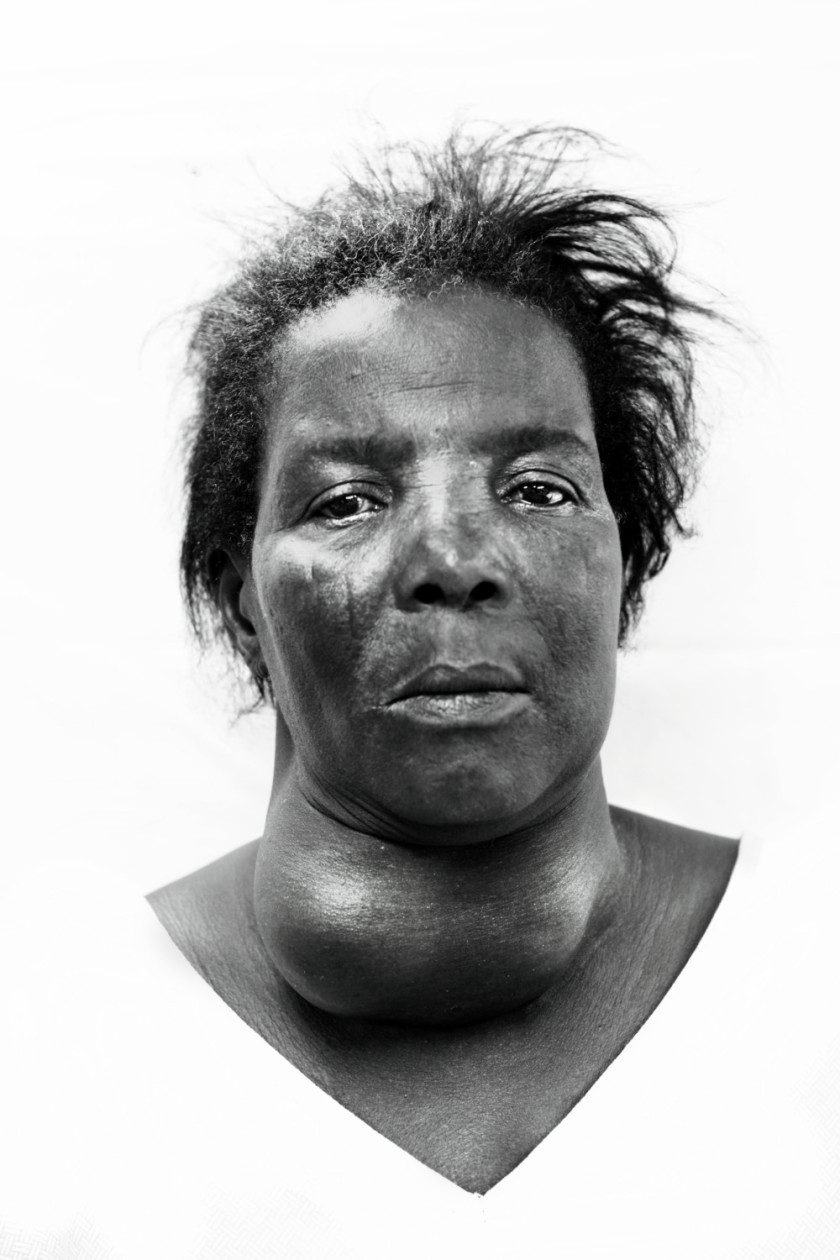

Before she attended a Mercy Ships screening Ayabavi was pushed around various health clinics, having tests and examinations delayed. Her tumour was very painful, and it was bleeding to the point where she was feinting. Eating was getting harder and the situation was clearly getting desperate. Her daughter heard about Mercy Ships screenings taking place in Aneho; they examined her, taking her to the Africa Mercy to get her tumour scanned. She was told that it was inoperable, but they could provide a palliative care team to help here deal with the pain and help her live the end of her life with dignity.

Before they started visiting she was treated as somewhat of an outcast due to the smell that the tumour was causing. She was weak, barely strong enough to walk 20 metres. She had needed a lot of help just to make it up the gangway on the ship.

The drugs, painkillers and dressings have helped enormously, stopping the smell, and giving her strength and her appetite back. Harriet, Alex and their translator (for the first few months) Sylvie have all become good friends of hers.

Her daughters are grown up and help look after her, changing her dressings when needed, and making sure she’s happy. She spends lots of time with her grandchildren, and will sit down and chat to other people in her village now that the tumour doesn’t smell. She’s taken Harriet’s advice about the best diet to have, but making sure your diet has plenty of vitamins is no comparison to the drugs and painkillers the palliative care team provides. Like Lucie and Eklou, these will run out a few months after the Africa Mercy has left, and she doesn’t know where she will be able to acquire more.

Ayabavi.

Ayabavi’s daughter Tante dries her eyes behind her mother, as the palliative care team talk about life after the Africa Mercy leaves Togo.

Harriet and Ayabavi’s daughters change the dressing on her tumour.

Alex plays with Ayabvai’s granddaughter.

Below three: Stalls at Ayabavi’s daughter’s shop where the palliative care team meet her each week.

Ayabavi prays with Harriet, Alex and Sylvie.

Ayabavi in her house.

Ayabavi’s room.

Ayabavi with a photo I took of her on my previous visit.

Ayabavi leaves the complex of houses where her home is.

The palliative care team in Togo was Harriet Molyneux, Alex Williams, and their translator Sylvie, then Komlan. They provide counselling and advice on how to live the remainder of their life, and are willing to pray and read the bible if the patient wishes. They can provide drugs and painkillers for as long as the ship is in dock and a few months more. The ship’s primary function is to provide surgical care in the areas of Africa where it is needed most. It left Togo to undergo five months of repairs and maintenance in South Africa, extending its service for another 30 years. Mercy Ships can’t help everyone, and leaving an area like Togo where they could clearly carry on working around the clock for many years will always be painful. However Togo is not the only country in need of their services, and once the ship is finished (hopefully in February), it will be going up to Sierra Leone to start a 10 month field service. I’m hoping to join them for a month or two out there.

One can only hope that Lucie, Eklou and Ayabavi leave this world without pain and with dignity.

(L-R): Komlan, Claire, a grandson, Harriet, Ayabavi, a grandson, Sylvie, Alex, Tante and a granddaughter.