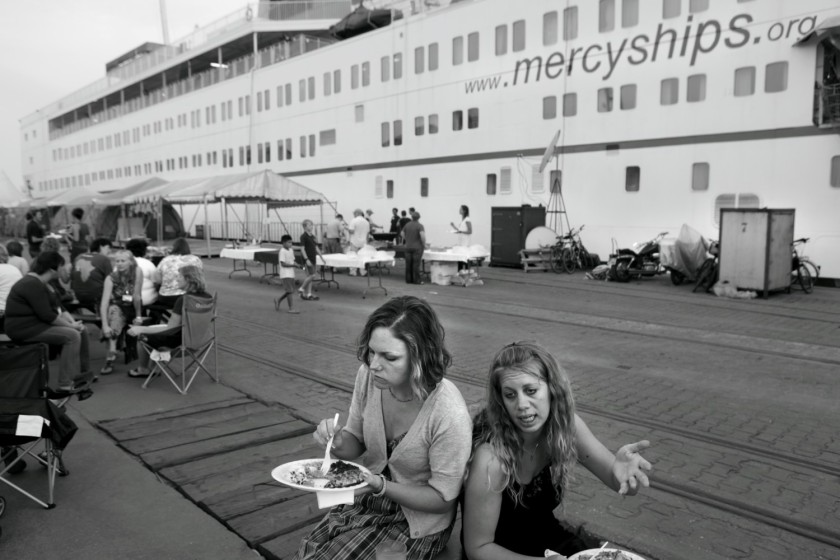

On Sunday 15th the Africa Mercy left port for the sail to South Africa where it will spend the rest of the year in dock suffering ship repairs of one sort or another. I had originally planned on going to Liberia or Niger to photograph more leprosy in these next three weeks. However, I wasn’t able to get a response from the contacts I had in Liberia, and the TLM (Leprosy Mission) reps I knew of in Niger were all going on leave from the 16th. Naturally.

So I had a choice – pay an extra $500 plus £300 for three weeks additional ship fees and a flight home from Durban which lets me spend extra time to work on various photo projects in the office I’ve called home while crossing the equator on a Danish ferry-turned-hospital ship designed for journeys of no more than a few hours. Or stay in Lomé as a guest at the house of one of the day volunteers who I’d only just met, but who runs a charity that aims to help the street children of Lomé which I could photograph for. As much as I was burning to sail for three weeks and spend that little extra time with friends I know I may not see for a long time, I decided the opportunity to get to know Lomé as well as photograph for a local charity was too much to pass up.

One of the Mercy Ships longest serving volunteers waves goodbye for the last time.

The gangway is lifted up – the point of no return (for me at least).

So I waved goodbye to the Africa Mercy. It was a strange moment waving goodbye to 100 beaming, colourful, familiar faces, some of whom it was very painful to say goodbye to. The port seemed bleak and empty without the blue and white branded hulk. I didn’t feel as though I was saying hello to a new adventure, just saying goodbye to the last one. It was like a huge vacuum had just been created in my life, ripping away all sense of comfort and routine that I had settled into over the past three months.

However I told myself I’d soon be experiencing what it is really like to live in an African capital city, away from luxuries like air conditioning and a dining hall with boiling water on tap. It would do me good.

There were about 12 or so of us left behind, many of whom were staying at the Team House (a rented complex where inland MS volunteers had been staying), one staying at a hotel for a week and myself who was meeting up with Raymond the day volunteer to go and stay with him, his wife, his puppy, and as it turned out his baby girl who was born the night before. I couldn’t help but wonder if I’d come at the wrong time. As I write this I unfortunately still have that feeling…

However, Raymond had insisted I stay with him. I believe it’s quite a nice house for this area of Lomé. Raymond has a spare room and his wife had already made my bed the week before the boat left by all accounts. He’s provided a mosquito net and curtain-come-sheet, but it’s so hot and humid that I need no more. The bathroom is two tiny cubicles – one with a toilet (I’ll spare details of cleanliness), and the other a tap with a bucket. It’s very cramped, and I don’t even mind that I’m washing out of a bucket. Trouble is I’m the only that uses toilet paper, the soap smells dodgy (I foolishly left my shower gel on the ship) and it doesn’t let in light, or have a working bulb.

My room.

For the first two nights his wife Vivienne and the baby stayed in hospital. His puppy, Joli was a month and old and very cute. It was nice to have a timid and totally clueless ball of dusty African fur to scratch and pay a bit of attention to for the first day. It stopped after that because the dog disappeared right before a day of solid rain. I’m guessing there’s 10 inches of lifeless pup-meat lying somewhere in the sewer ditch that runs past the back of the house, right outside my bedroom window. On top of this, calls from the hospital kept coming through that Raymond had to go and buy drugs for his wife and the baby, who had a fever for the first few days – a worrying time for any child in the developing world.

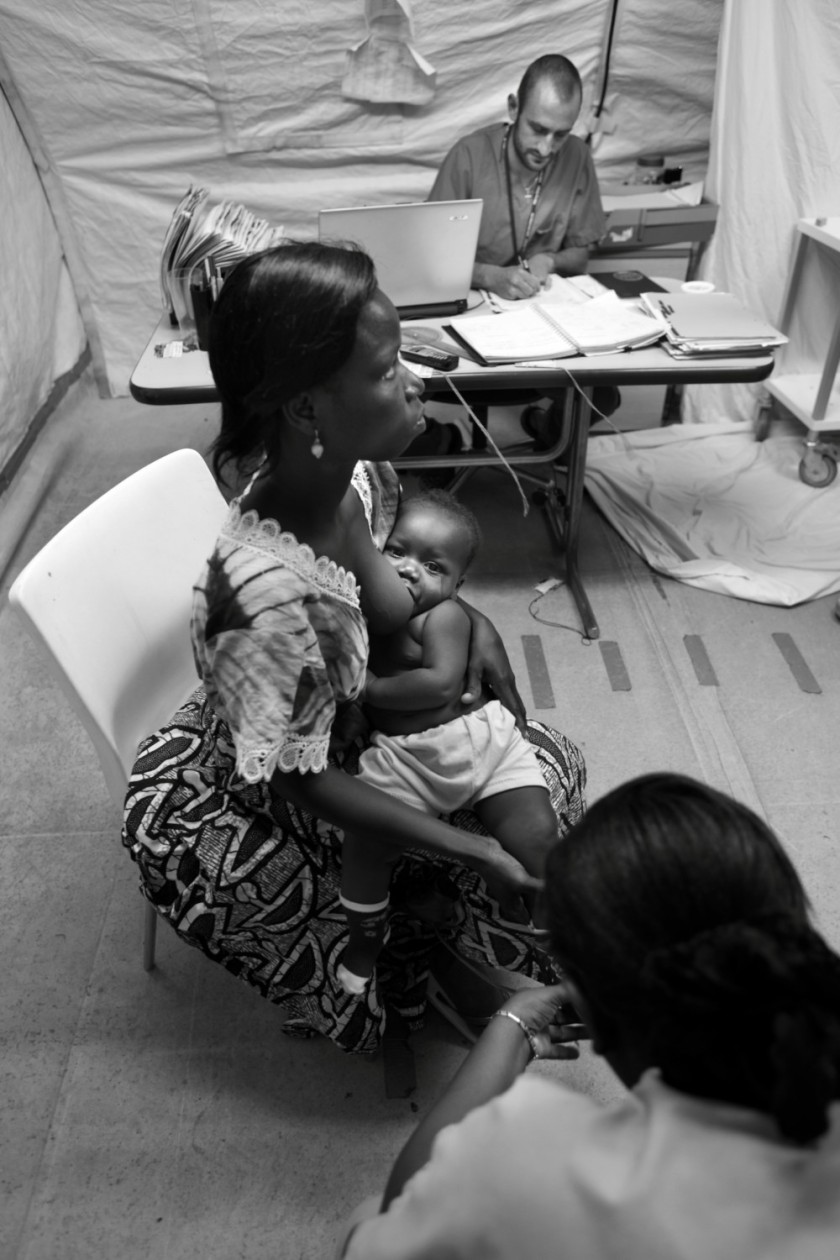

I made friends with quite a few day volunteers in my time with Mercy Ships. These are men and women from Togo who are paid expenses and a small (but not bad for Togo) wage to work on board the Africa Mercy in various positions in various departments, mainly as translators, but also as deck hands, cleaners, galley crew etc.

I will eventually post a blog about the day volunteers leaving party. It was a sombre time for most of them, who are going back to a life with no jobs. The same is for Raymond. He has his charity, UNICODES which was set up in 1999, but got all the official paperwork done in 2007. I’ll explain more about it in a few weeks, hopefully after I’ve taken some photos that describe what they do – essentially they are aiming to combat the problem of youth on the streets, many of whom have no home and are forced to resort to illegal activities like stealing and prostitution. He is hoping that UNICEF will fund the work the charity is doing and will allow him, as president, a small wage. He has a program written up, along with a number of staff that are willing to be trained and a comprehensive (apparently) budget. This will start next year if he gets funding.

Meanwhile, I went to and fro on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday trying to get a visa extension sorted (successfully thank goodness), having to get a new charger for my laptop to replace the one that didn’t work except for the occasions when it sent off sparks, and trying to figure out what it is that Raymond actually wants me to do for the charity.

I’d already offered to cover expenses for my stay, Raymond asked for some money up front to cover the next two weeks at least. This would cover all travel by zimi-jean (motorbike) as well as my portion of the food that I’d be eating with the family.

On the first night when it was just myself and Raymond, he showed me how to cook a gumbo (okra) and fish soup with Akumé (the pap similar in consistency to fufu, but with flour added as well). That lasted a few days until his wife and mother-in-law returned. The mother-in-law (which she was introduced to me as – I call her grandma) is a very sweet old lady, and between her and Vivienne, the food has been absolutely delicious. They haven’t so far cooked me anything that I haven’t loved. No ‘problems’ yet either (famous last words).

Looking out of my room one evening.

Grandma.

The baby under her mosquito net.

The baby, who has been named Robin (after Robin Harper if you’re reading this!) has hardly made a sound, except for when grandma was throwing her up in the air and catching her. Upside down.

Raymond at a UNICODES meeting in his house.

Those first few days were incredibly frustrating, but that gets easier once you realise Africa requires endless patience (I thought I’d vaguely learned this over the past three months when going off ship with Mercy Ships). I can safely say now that Mercy Ships perform miracles with what they are able to coordinate and achieve with the countries they work in. It’s still frustrating, but I’ve since learned just to roll with it.

I have been out on only two trips to photograph around town since I’ve been here, which has been disheartening, I must admit. I’d got the impression from Raymond on the ship that he’d already organised all the different places and people to photograph. However, this is Africa, and it’s never that simple. It seems that in these next few weeks we should work to build up a relationship with children to gain their trust before photographing them. I couldn’t agree more – I’d just assumed that Raymond had already done that with some of the children. In all fairness, it’s been hard to gauge all the facts about what the charity has done without appearing to be an interrogator. Raymond seems to have a lot of last minute meetings (political, church, family, anything…) that either overrun, or don’t start on time (usually both), that coincide with when we were supposed to go out and photograph, so I’ve been out twice to photograph street children. Once with Joseph, a friend of Raymond’s who is quite timid, and submissive (as Raymond put it), but who owns a zimi. Unfortunately, he didn’t seem to understand at all what I was supposed to be photographing (a general mystery it seems…) so I did my old bit of street photography through the market.

A naked mad man who some Mercy Shippers maybe recognize from the streets.

Selling pepper’s.

Muslim’s wash their feet before worship.

I went out the next day with Raymond, and got talking to a few street kids on the beach, finally getting one or two decent photos that could possible relevant to this project (whatever it turns out to be!). I won’t post them now, but here’s a few along the beach…

I was hoping to meet them again today to get to know them a bit better and gather some information as to the sort of lives they lead. They were for the most part very friendly and eager to be photographed. I will say one thing for Raymond, as I’m sure anyone who knew him on the Africa Mercy could vouch for: he is an excellent talker and gets along extremely well with children. If I knew that we could go out for 5 hours a day to meet and photograph children (as I had naively thought it might be) each day for two weeks, I’d be confident of creating a coherent and interesting photo essay about the street life of a child in Lomé. Maybe coming events will surprise me. I’m sure I will get an interesting series of photos that show life in Lomé, but it would be nice to make sure I go beyond that and actually get photos that a struggling local charity like UNICODES could use to improve its image – make it look that little bit more professional.

In all honesty, I do love it when we hop on a zimi and zip through town; the wind dusting my beard and blowing my hair into a jedwardesque hairstyle. I’ve travelled on zimi’s quite a lot in Lomé and I’ve only ever come across one that had working dials on the dashboard. It was also spotlessly clean. However that same guy had also angled both of his mirrors so he could see his face from both sides, and not behind him. Maybe that doesn’t matter too much, as most of the others didn’t seem to have mirrors on their zimis anyway. There’s something very liberating about hopping on the back of a motorbike and zipping in and out of traffic, experiencing the sights and smells of Togo. It is one thing I know I’ll miss about Togo.

It is exciting going out when the African rain hits. You wade through miniature street rapids and after the downfall the mud roads have changed; the meandering grooves that plague the taxi drivers and make life more fun for the zimi drivers deepen and form little ox-bows in the street. And in some areas the stench of human waste thickens in your nostrils until you simply accept that you can’t do anything about it. It helps squeeze the squeamish out of you.

I’m ashamed to say I have not made nearly as much effort with getting to grips with French as I should have. Having translators around has spoilt me. However I’m trying to learn as much Ewe (the local language) as I can – Raymond’s teaching me but I’m not the best learner. Bizarrely though he’s been taking me to a free Chinese language course in town for two hours day. I asked why we are going, to which Raymond grinned ‘because it is what I want very much to learn!’. Obviously.

So myself, Raymond, and two others can count (extremely slowly) to nine hundred and ninety nine million, nine hundred and ninety nine thousand, nine hundred and ninety nine in Chinese, as well as say the basics; how are you, I’m fine/have a body with no health etc.

Vivienne speaks a little bit of English, but Raymond is really the only person around that can translate for me and I can have a decent discussion with. He has a lot of energy and a good heart. Unfortunately on Saturday, when he was supposed to be at a political party meeting we got a call from him saying that the mild malaria he thought he’d had for the past two days had got much worse and he was in hospital.

Vivienne and I left straight away, leaving grandma and the baby behind. When we got there, Raymond was on a dirty table-bed, with no doctor in sight. He had tears in his eyes and was no longer able to talk or even open his mouth, and he kept pointing at his heart. What really makes me angry, and is the icing on the cake of why I’ve written this post is that his wife was given a prescription and told to go and buy the prescribed drugs for him, as well as glass slides and a tube to take a blood sample. If his wife had not been around, or if they didn’t live in Lomé there would be no one who could have got him any pain killers, or medication or anything.

Everything here is just so bloody inefficient.

I have given my last bit of cash on me (about $20 worth of CFA) to his wife that will hopefully cover the drugs. I did not hesitate in lending/giving money for his medication (as I’m sure any person in my position would have), but at the same time part of me didn’t want to – because what would happen if I wasn’t in Togo staying with Raymond? Would his wife have stood and watched him suffer pain until it went away, or perhaps it is not worth thinking about. I am thankful that I’m privileged to be in the tiny top percentile of the world that has as much money as I do, even if it does not seem that much to me. I am a white westerner. And the fact is that I am in Togo, I am staying with Raymond and I will do what I can to help without being too foolish.

Even speaking to those from the states on board the Africa Mercy I realise how lucky the UK is to have the NHS. I’ve had a number of operations in my time, and I’m sure if my parents had had to pay for them life wouldn’t have quite been the same. I don’t think I’m being overdramatic.

It turned out that it was malaria, and the IV medication, thankfully did help. He’s still resting, but feeling much better. I’m sure if it was me that got malaria I would not have recovered so quickly.

I’m experiencing the real Togo, and in this past week family life has been as colourful and chaotic as i could have imagined it. I am learning that the life of a local in Lomé is about enduring constant frustration, pain and crises, while learning that the best way is to just roll with it, trying to enjoy the occasional carefree feelings of freedom, and balance a careful mix of not planning ahead with planning too many things at the same time (not planning ahead seems to work better I think). And I am extremely thankful for where I come from, and where I will be returning to in 17 days. I am glad though that I chose to stay in Lomé and not sail. I’m sure I would be enjoying the sail thoroughly, but my desire is to live Africa, not the 51st state of America.

Meanwhile I can only hope things improve while I’m here, for Raymond, his family, myself and this slowly evolving project.

If you could spare any thoughts or prayers for Raymond and his family it would be greatly appreciated by them. Thanks, Tom

![_MG_7876 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_7876-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_7951 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_7951-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_7968 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_7968-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8035 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8035-1500x15001.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8078 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8078-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8146 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8146-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8235 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8235-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8314 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8314-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8505 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8505-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8616 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8616-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8792 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8792-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)

![_MG_8798 [1500x1500]](https://tombradley.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/mg_8798-1500x1500.jpg?w=840)