The trip up to Sokode went as far as I was concerned pretty smoothly. Dodji and I left the house at 6 in the morning and went straight to the bus station where I bought us tickets up north to Sokode. I’d travelled on plenty of local buses in various part of Africa before, so wasn’t surprised that we had to wait for over an hour for the bus to leave at 7.30am. I also wasn’t surprised that it didn’t in fact leave until 8.30am. In fact I was pretty happy it was only delayed an hour. In Zambia I once had to wait 8 hours for a bus to leave after its scheduled departure. Naturally we were crammed into the bus, 20 in a 14-seater bus. Raymond (having lived in Sokode for three years) had promised the journey would be about three hours. I remember smiling to him as he said this and suggesting that perhaps it would be therefore more like five or six hours. I received a hurt look in return and bit my tongue from explaining the western take on time in Africa.

Regretting my smugness we arrived in Sokode at 4pm. There weren’t even long delays, we stopped every now and then for travellers to answer nature’s call and satisfy their snack cravings as well as allowing a poor young mother on the bench behind me to clean her vomit from her and her baby’s clothes. Malaria apparently.

After directions from a pastor-friend of Raymond’s to Koloware, where the Catholic Mission Leprosy Centre-turned Health Centre is located, we hopped on zimis for the pleasant journey through beautiful lush-green Togolese countryside. The villages were beautiful, with noticeably less rubbish than near the cities and stop-off points on the journey up. The wind blowing in my face was warm but not to humid, the clouds ranging from bright white to thick black, divided with crackled lines, a sky that had Ride of the Valkyries as its soundtrack. Raindrops fell lightly and sporadically bringing the temperature down perfectly.

We arrived at a Health Centre that looked luxurious – spacious, clean simple buildings that were not nearly as old as I had expected from a leprosy mission that had no ties with NGO or government funding.

We briefly saw the director, Sister Antonietta, who was extremely busy, but greeted us with a beaming, surprised smile. It was through a friend of Raymond’s who worked in Health that I had heard about Koloware. When I asked for the number to call ahead and ask if we could stay, he said it was not a problem – it was run by Catholic sisters and they had a dormitory. We could turn up, explain my project and stay there with no problem at all. I’m not sure the frightfully busy Sister Antonietta quite appreciated his casual attitude. Explaining that she’d been given no warning, she informed us of the lack of beds they had at Koloware – even all the hospital ones were full. We’d have to put ourselves up in hotel in Sokode. Well I was not able to afford the daily commute to Koloware for the next couple of days let alone accommodation at a hotel – even basic accommodation was not within my budget for the trip.

With nowhere to stay, Dodji and I stood crestfallen at the side of the road – the formerly pleasant light rain now soaking through our clothes and spirits. He explained our situation to two passing elderly gentlemen. They sympathised and led us two minutes walk away into a little hamlet of huts. There we were introduced to Reda, who immediately with the fussiness of a grandmother who had just had the Queen turn up on her doorstep took my extremely heavy camera bag and sped across a courtyard over to a room while excitedly beckoning us to follow. In less than five minutes, with barely a word from Dodji or I she had cleared the room, put in a hefty mattress made with rice bags for myself, a mat for Dodji (he insisted on sleeping on that rather than the mattress), clean sheets and a table for all our things. We thanked her constantly, but she just said ‘non non non non non’ waving it away.

This is Reda's courtyard. Our room is the centre one with the door open. The man on the right is brewing beer.

Reda cooks our Akume and Soup by torchlight. Electricty went down 3 months ago in this area from a lightning strike. It hasn't been fixed since. Only the hospital has it's own generator.

Half an hour later, we were clean (I’m surprised at how I’m now so used to washing with cold water from a bucket) and sitting down in the dark to akume (a mashed pulp of cassava and flour) and kodoro (a northern Togolese soup made with leaves from baobab trees). I really couldn’t have asked for more.

A 6.40am rise and we went straight to the health centre where Sister Antonietta pointed us in the direction of the leprosy clinic. There were already 15 gathered together, ready and waiting for wound care and dressing changes by the nurse Tchedre Wallakosona. It took a little while to find someone who spoke French well enough to translate into the local language of Kotokoli.

Eventually it was Kufou, the pharmacist’s son who was shyly pushed forward. With two translators, especially when one is 13 and only speaks the French he’s learned from school, it’s not always easy to get the answers to the questions you asked originally. Still, I managed to talk to a couple of patients for a while, gathering their stories.

Dodji speaks to Mahammoud, a blind Beninoise leprosy patient that has lived here for over forty years.

The rain was thick in the morning, getting to torrential-standard for the UK, but simply averagely-heavy rain for here.

A decent rest at lunch time and a quick charge of my laptop at Tchedre’s house made for a relaxing afternoon before more photography. I got a chance to chat with the spritely, enthusiatic Tchedre, who proved to be extremely helpful and informative about the health centre and the area. He’s worked here since 1967, and despite the fact that he officially stopped working 5 years ago, still works with the leprosy patients in the hospital three days a week. I’ll follow up more on this in my next blog, specifically about the leprosy work being done here.

The Togolese people further north in the country are, like many western African countries, predominantly Muslim, and I attended my first ever Islamic event in the evening. The Imam allowed me to go into the Mosque and photograph. Embarrassingly I know very little about the religion, so I was cautious and hovered at the back, photographing in the spacious, well-used room, the light blues and drab browns lit by just a couple of bulbs. It lasted just a few intense minutes, with the Imam praying out loud at the front. Each time they bowed in silent worship I’d take a photo, aware of the echo of my near silent shutter in the holy temple.

I nipped round the back to photograph the women’s entrance. They have a separate area at the back where they pray. I’ve always wanted to find out more about Islam, preferably not from reading the Daily Mail, so if anyone has any recommendations for a book about it I’m all ears.

Dodji and I got back to our room in the dark to find a mouse in my mosquito net and droppings all over my bed. I’m not particularly bothered about such things, but Dodji had a little fit trying to stamp on the mouse which promptly disappeared into the corner of the concrete room without a trace. A half kalabasse bowl was posted outside Reda’s, informing passers-by her homebrew was for sale. I tried a bit with my Akume, it smelt like rotten vegetables, but tasted more like very yeasty liquid bread dowsed in something strong and tesco-value. I declined a second bowl.

My wash in the square walled drainage area across from the little courtyard was shared with a spider the size of my palm, pulling itself up into the tree above on its slivery thread, glinting in the light of my headtorch, and unwavering in the warm still air. The yellow markings on its back glared at me, just daring me to have a reaction. I’ve barely seen the stars since being in Togo, a result of spending most of my time among city lights, but they are clear up here deeper into the country, peaking through the branches above my head. Venus shone out like a pearl among salt granules, with the dim orange hue of mars not too far. I saw several shooting stars, and not a single satellite. For the first time in three weeks, I wished I could stay here a bit longer. This is the Africa I’d like to live in. We went to bed early, to the laughs of men outside drinking Reda’s homemade beer.

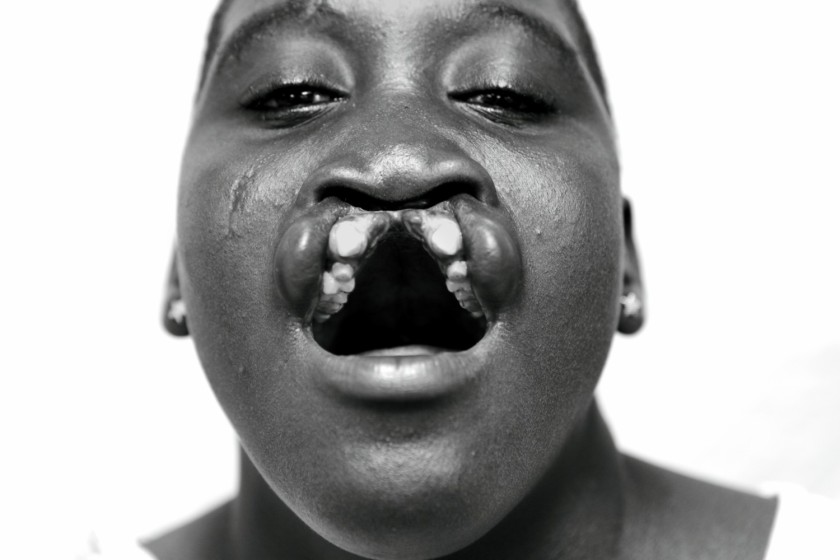

Saturday was market day. The market only started to get under way at about midday so Tchedre showed us around several houses in the morning, asking many of the leprosy patients if I could photograph them. I spent two hours with them, as well as photographing a few around the market. I’d already established from Tchedre that despite Koloware having a large concentration of leprosy since the late forties, and the town also being educated in the fact that none of them can pass on the disease (as none of them are carrying the bacterium) there was still a large stigma attached to having leprosy. Almost all the ‘lepers’ get children or relatives to sell their produce in the market to avoid being seen; it is only a few that venture out to brave shuns and revilement.

I had the idea in the afternoon of photographing Mahammoud, one of the patients I had spoken to the previous morning. He agreed to stand without his sunglasses or prosthetic limb wearing just his shorts. I photographed different parts of his body in sections. I’ve exhibited my leprosy work before, and am always looking for new exhibition ideas, and a montage of close ups of this man’s frail, weathered body, numb from leprosy, still healing from wounds well over a decade after he went blind I’m sure will provoke a response from the audience.

He was more than compliant about posing, and I helped him put his prosthetic limb back on afterwards. He’d mentioned the day before that of the five people living in the housing block, he was the only one who had no relatives or friends to visit him. Usually I don’t give money to those I photograph, especially just one person, but since it was beer season, I gave him 200CFA (40 cents) to get a bowl from where everyone else was on this swelteringly hot market day. A big grin broke out on his face, one that you might expect from an old man at the end of his years who’s just been given the opportunity to spend a hot afternoon with a kalabasse of strong yeasty-red beer. Who can blame him? Being blind, disabled, very forgetful, going deaf and with no relatives to visit him, there’s little else left in this world for him.

On my last night there it rained. This time the rain was torrential. It started around midnight and carried on through the morning. For about half an hour it was truly deafening. I was awake anyway when it started, and heard the first few dull thuds like small balls of putty falling from a great height. This developed in a matter of seconds into a barrage of paintballs fired from the heavens targeting Dodji and myself. Within ten minutes it seemed like waves were hitting the house, the Atlantic Ocean emptying itself onto our doorstep. The corrugated iron roof amplifies the sound five-fold and I spoke just to see if Dodji could hear me. I could barely hear me. With the exception of slight cracks around the wooden door and window shutter, the room was sealed, yet I could feel the spray through my mosquito net. I’ve always loved storms, but this one never subsided, and when my alarm went off seven hours later I realised it may be a wet journey to Sokode.

I’d planned to say goodbye to Tchedre, but with the rain like it was I’m sure he’d understand that we’d have got drenched going to his house. Luckily there was a car by the bar down the road that said it had two spaces. It’s not so much hitch-hiking, as anyone can be a taxi, so we agreed about $2 for the both of us to Sokode and hopped in a car that was in poor condition even by African standards. The windscreen resembling a crazy-paved patio is a norm and not something to write home about (he says writing home about it). The front seats looked like they had been attacked by a starved Rottweiler on crack and the back of the rear bench looked half melted. Dodji’s door had to be tied and untied in order to get in and out of it, and mine kept swinging open. Luckily this wasn’t too dangerous as we couldn’t go much faster than 20 mph, partly due to the 100kg of charcoal propping up the back seats, and partly to do with the ancient engine that had a break to smoke every 20 minutes (the driver kept pouring something into the bonnet to put out whatever fires lurked underneath). It had taken us 25 minutes to get to Koloware, but over an hour to get back to Sokode.

The trip home was lengthy (we had to wait 4 hours for the bus to show up this time), but being on a large (prebooked) coach, it was much more comfortable. I got home at 8.30pm to Raymond welcoming me with open arms, like I was the prodigal son. After Koloware, Raymond’s house seems very modern and comfortable. Just goes to show everything in this life is relative.

This year’s adventures in Africa have come to a close now. Raymond, his family and Dodji and the other people who have introduced me to life in Togo have been extremely kind to me and I will make every effort to stay in touch with them in years to come. The last three weeks will stay with me for the rest of my life as very strange but essential time in getting to understand a bit more about how most of the world lives. Yet I don’t consider the wildly poor (compared to back in England) houses I’ve stayed at as places of poverty in terms of the other things I’ve seen here. Perhaps next time I’ll have a go sleeping on the streets.