This is the Congo.

As I sit down to write this in Dr Jacques Kongawi’s beautiful little guest house (though larger than his own modestly-sized quarters), the rains begin to beat down heavily outside. The corrugated iron roof acts as an amplifier; a huge African drum under a million drops of rain. The volume of noise is incredible. This is the sound of the Republique Democratique du Congo, famed for its mighty river (above), just a few months into the long rainy season.

I am in Gemena, a town in the Sud-Bangui province. On a map of the continent this is the bullseye. The DRC (as English abbreviates it to) is the country that probably has the greatest wealth in terms of natural resources in the world. But instead of becoming a rich, healthy nation it has been plagued by greedy Kings, colonialists ruling with an iron fist, absurd and almost laughably selfish dictators, bloody and complex wars, disease, and everything else that stands in contrast to the great potential it has to becoming a prosperous place to live. Rape is redefined in the Eastern parts of this country and it has been declared to be the worst place in the world to be a woman – in an age obsessed with Al-Quaeda and the Taliban regime that is quite a statement.

But for the month of June I have been documenting a problem that has been around long before the Portuguese explorers first ventured into the mouth of the great river natives called Kongo.

I am working with American Leprosy Missions, one of a number of organisations dedicated to dealing with the problem of leprosy worldwide. I spent 4 days south of the capital Kinshasa with their Buruli Ulcer projects – a nasty ulcerous bacteria similar to leprosy but much more painful to its victims – before moving up here one week ago, to the largest concentration of leprosy in the country. I arrived with Bill, president of the American Leprosy Mission, Matt also with ALM and Nikki with The Leprosy Mission Canada. Most of the photographs in this post are from many short visits to patients we did in the first week so the team could collect stories on video and assess how best to direct their funds. Bill is new to ALM, so it was also good for him to see their projects first hand.

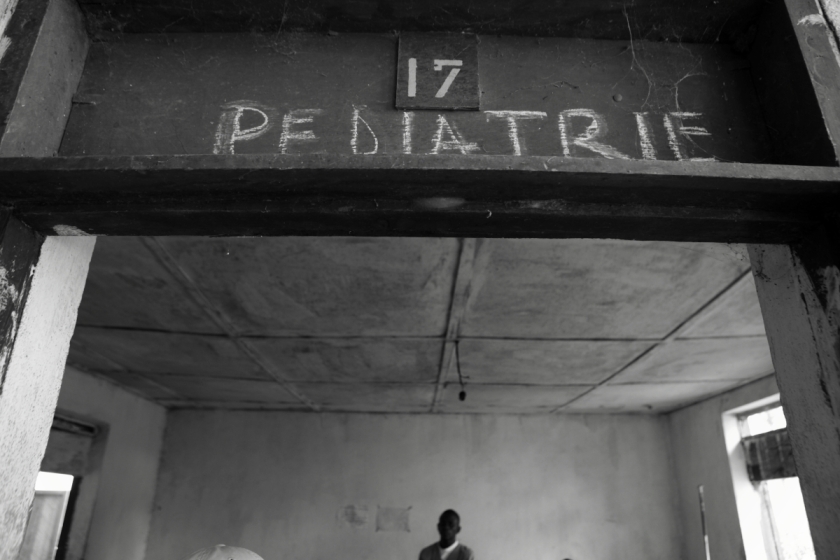

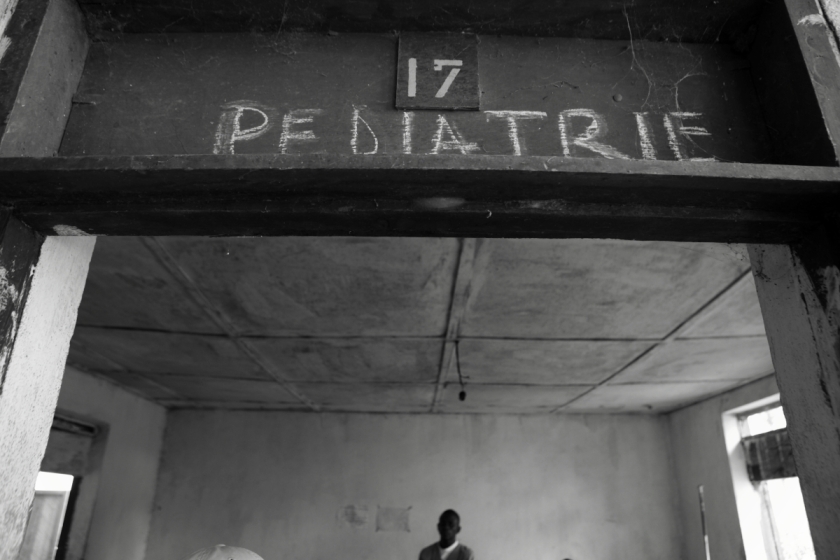

Above: the sign on the door of the leprosy office in Karawa hospital a few hours bumpy drive from Gemena.

Photographing leprosy across the world has become somewhat of a personal project of mine, and I’m hoping to document it in other countries next year. It’s a disease that everyone has heard of – everyone knows about Jesus healing the ‘lepers’ whether you are Christian or not – but generally across the world, even in the countries where it’s still present there is very little basic understanding, and sometimes even awareness that it’s still a problem. I’ll give you a very brief rundown…

Leprosy is curable. The culprit is Mycobacterium leprae, a bacteria closely related to tuberculosis. It is thought to be transmitted in water droplets – perhaps through sneezing for example, but it is not that easy to contract. It is clear that you have to spend a long time with people affected by leprosy to stand a chance of getting it. You also need a very poor immune system. Despite spending long periods of time among these people I will almost certainly never get it. When it does manage to survive in a human it takes around 7-10 years before the first signs of leprosy emerge. These are usually skin patches that begin to show signs of anaesthesia. The destruction of areas of the peripheral nervous system is the best know symptom – it means that any cuts obtained in these numb patches don’t get noticed. They therefore aren’t cared for, they don’t heal well and infections develop; flesh rots away or requires amputation or excision. It is this that can lead to the characteristic missing digits or limbs that are associated with leprosy.

But start taking the antibiotics that is provided for free worldwide and within a day 99% of the bacteria is eliminated from your system and you are no longer contagious. To totally rid of it, continuation of the Multi-Drug Therapy (MDT) for a year is usually necessary. However any numbness attained or digits lost will not change and for the rest of one’s life great care must be taken to make sure any cuts suffered do not get infected.

There are many different problems and reasons why leprosy is still present worldwide, despite it being ‘officially eliminated’ from all but three countries (Nepal, Brazil and Timor-Leste if you’ve ever heard of it). I won’t go into those reasons here… I could cheekily refer you to my own website where I have explanations along with photo essays that go further into these problems, or alternatively please click on the brand-spanking new website of the American Leprosy Missions.

But right now I’m in the Congo and in my brief week I’ve had the chance to visit a number of the different people that have at one point suffered this disease. Some of the stories are extraordinary.

Mitano, an elderly man with leprosy sits in the house that ALM built for him. He now keeps a couple of chickens and a rabbit. However every now and then people will steal from him, so Dr Jacques, the Regional representative for ALM, decided to buy him a dog to scare people off. He named the dog Dr Jacques. He has suffered a lot of stigma, and has never been invited to any of the local community gatherings or occasional celebrations. So recently he decided to spend all of his money on hosting his own party to see if people would turn up. He bought meat and fish and was amazed that residents came along to eat the food he’d prepared with his own filed-down hands. He broke into a grin “When I am at last taken away from this life, they will put on my grave ‘he hosted the best party this village has seen!'”.

Above: Gemena, down from the main market. I can’t personally verify Gemena is no different from any other Congolese Town, but I would imagine it works in the same way. When we arrived, Jacques turned to us all and pointed out a few places. “This is the post office” he stated clearly in English, but with a slightly nasal Congolese accent, “it does not work”.

Dr Jacques himself has many interesting stories. He is one of many half-black half-white Congolese whose mothers were the ‘local relief’ Belgians indulged in during colonialsation. He managed to become very well educated without his father who had visited his mother a number of times over the years. When he was in Brussels studying Tropical Medicine on a scholarship he found out his father was not dead like his mother had been informed by a Belgian nun. He found out the address, and when a woman answered the door, left with her a written message explaining he was the son of so-and-so. When he returned he was told to leave immediately before the police were called. He never met his father, and never wanted anything from him other than to see his roots. He has friends with similar stories. He remembers one childhood friend who was taken from his mother to be adopted by a Belgian doctor and his wife who couldn’t have children of their own. The mother was told her son, who was at the doctors for a few days had died in the night. She of course could not even see the body. This was all found out many years later.

Above: family in Africa is very important… this elderly woman with leprosy (centre) claimed to have over one hundred grandchildren. We somewhat doubted, but considering you can be Catholic and still have several wives here it is unsurprising that people often have ten children. There is one man in Gemena who has apparently fathered 48 children.

This is Nzalawa Albertine. She is probably in her fifties, but isn’t sure. Her first husband died in the nineties. She has given birth to 17 children in her life. Four of them are still alive. She blames her second husband for the death of the other 13. “My second husband and his family used witchcraft to kill them. I do not know how, but I know it was witchcraft”. They died for various differing but not unusual reasons… mainly from falling sick. Strangely though, she said her husband admitted to killing the children (mostly from her first marriage) through witchcraft. This is a part of the culture that is initially hard to accept as a travelling westerner, but one I’ve know seen in other countries like Togo, Benin, Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

She states their deaths quite matter-of-factly, numbed perhaps from each loss. The numb patches from leprosy on her feet and body add to an already unbearable burden. She got leprosy shortly after she fled her second husband, unable to have any real say in the divorce she wanted. After all, this is Africa, and she is only a woman.

She lives with one of her remaining daughters. She used to shelter in a ramshackle hut until ALM built her a more solid one. She spends all day farming cassava leaves and occasionally manages to sell a few trade goods that ALM loans her… dried cassava, coffee etc. “I eat cassava leaves every day. I have no money for oil or salt, so it doesn’t taste of much.” Dr Jacques furrowed his brow in concern and asked a question he very well knew the answer to. “Do you ever have a chance to eat meat?“. Nzalawa laughed weakly. “Who will buy me meat? Without my daughter here I wouldn’t be able to do anything.”

I sit back and watch as Nzalawa carefully makes and filters freshly made coffee from the local beans. They give her the impetus she needs to get back to working in the field in the afternoon. Smoke fills the small but sturdy hut. She says her daughter is only 17, but she could be mistaken for being in her thirties. She was asked by a family in another village to be a man’s wife, but her mother said she couldn’t go because she depended on her so much.

I was amazed at how good some of the roads around here are (occasionally). Considering the infrastructure in this country is barely in existence I’ve been very impressed by the (occasional) smoothness of some of the roads. It doesn’t stop other areas resembling a particularly choppy sea though. “You know how to tell if a driver is drunk here in the Congo” says Jacques, his eyes smiling behind his tinted glasses. “They are driving in a straight line on the road”. Not that it would make a difference with the reliability of the police in this country. A man driving along the road who has spent all his money on palm wine has nothing to hand over…

The size of the trees and lushness of the vegetation in general around here is incredible. The agricultural potential, even on a small sustainable level, is enormous. Yet I see large factories still capable of producing vast quantities of coffee or maize, lying unused. No-one knows how to use them. They were taken away from foreign hands during Mobutu’s long regime, but there was no hand over and production ceased soon after the ex-pats left.

Above: In reading a bit about the history of the Congo I’d heard about this distinctive hairstyle typical of more central African countries. You see this style of braiding everywhere.

On Friday I visited Bulu hospital a couple of hours away, mainly just to see the state it was in. There were two leprosy patients currently under its care, but all the beds were full, and there were more urgent cases that took priority.

One of the patients visited while we were there so that Jacques could speak to them.

It was just such a poor rural hospital. The sterilised sheets in the operating theatre were tattered from use and stained so thoroughly it gives you goosebumps to think of the operations that caused them. Outside the maternity ward I found a young pregnant mother resting in a chair, her toddler waiting for her to muster the energy needed to pay attention.

Before going out one day a man came to Dr Jacques house, where I am staying and also where the ALM offices are. On average there are usually five visitors per day asking to see the doctor. They all have a patch on their skin and are afraid it is leprosy. We were on the cusp of leaving so Dr Jacques examined him on his drive, his well-kept property our of prying eyes so there was enough privacy still.

Naiya Yembe, 37 showed Dr Jacques the skin patch on his back and and also demonstrated the swollen nerves on his knee. Though he still had feeling on his patches the evidence pointed to early signs of leprosy.

Then the regional nurse walked in and he recognised Naiya as a leprosy patient that had been put on the MDT medication 7 years ago. He had taken the medication, but only for three months. Why? We told you to take the full course, what made you stop?

“I was running from the rebels. They came and we had to leave quickly so the medication got left behind”.

Naiya, his wife and his four children lived in the bush for two months waiting until they could safely return home. During that time his two youngest children got malaria and died. The skin patches had subsided and until recently the leprosy was forgotten about. He will start up the treatment once again after a laboratory test confirms it is leprosy.

An brief outing at sunset showed us a few of the areas around Jacques house. A beautiful lake provides the ideal dusk wash down for locals, their antics once overlooked by ex-pats enjoying a beer at a well-known Belgian restaurant. Abandoned during the Mobutu years, it still has in its grounds the majestic statue of Nzomba, a heroic local warrior, now only admired by boys who enjoy the view from the top. Even if the restaurant could get up and running, there are few around that could afford even reasonable prices.

More sinister territory lies near by Jacques house. This is the home (or one of them) of Jean-Pierre Bemba, one of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s more bloodthirsty politicians/warlords. He owns an enormous plantation next to Jacques house, just one small source of a wealth thought to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars. If he wasn’t currently awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court in the Hague for crimes against humanity and war crimes, we may have given quadbiking through his plantation a second thought.

We were eyed somewhat suspiciously by a semi-alert guard when we viewed his father’s mausoleum however. The concrete hexagon closer resembling an unfinished miniature silo than a grand tribute to is father, and surrounded by rust-red termite hills, it was a rather strange resting place for Jeannot Bemba Saolona, the wealthy Zairean businessman who profited hugely during the Mobutu era.

Clearly without Bemba’s presence, locals aren’t averse to messing around in the irrigation pools.

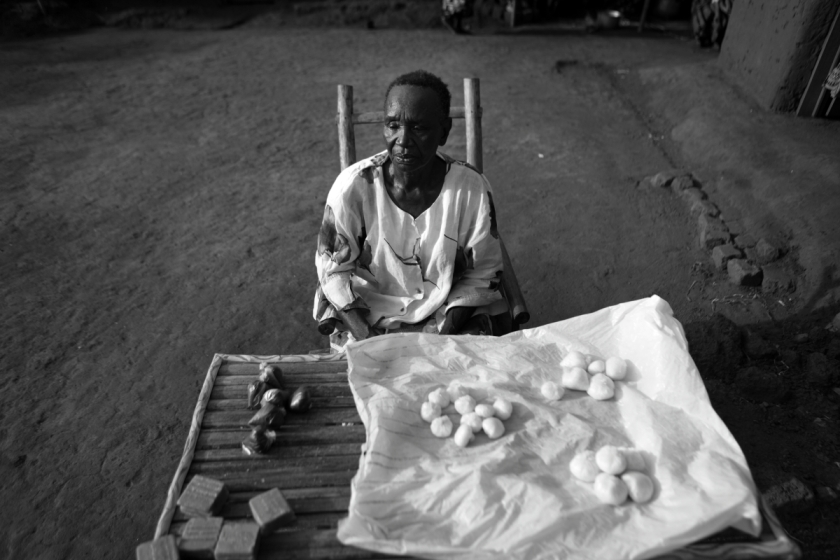

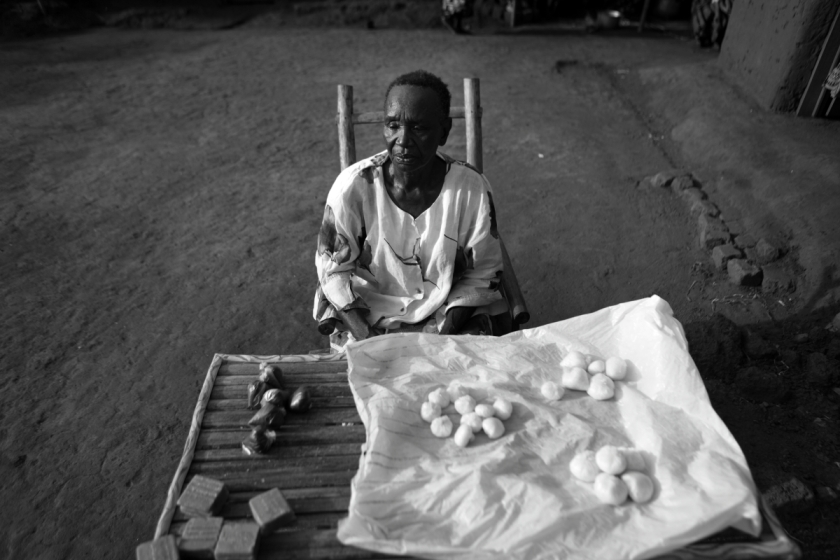

One of the ways ALM has been exploring in helping make the leprosy affected live sustainable lives is loaning goods for people to sell at a profit. These are usually along the lines of palm oil, salt, sugar, coffee and soap.

This is often done quite successfully. During the first week I saw two people repay recent loans from ALM.

However it doesn’t always work that way… one of the many challenges Dr Jacques must cope with.The pastor preaching to the crowd (above) had leprosy. ALM loaned him money to start a small trade, and enough to send his son to school. However, as I’ve noticed is increasingly (perhaps?) common across Africa, the money was spent on local brews. He is an alcoholic, and Jacques has had no choice to cut off money until he can see the man is attempting to make changes for himself. He says he needs money to send his son to school, but Jacques knows that there’s only one place that money will go if he is loaned it. The boy is, quite bluntly, collateral damage.

Expecting an alcoholic, much less one who still suffers after affects from leprosy, and who, as a given lives below the international poverty line to suddenly become sober, even for the sake of his son’s education would take nothing less than a miracle.

Above: strips of leaves used for roofing are laid out to dry in the sun.

Below: A man takes plantain and cassava leaves on the back of his bicycle to sell at a market 10km away.

Witch doctors, the local herbalists and traditional medicine practitioners have often posed problems, as locals usually approach them first if not out of preference, out of proximity. However some have been asked to refer patients that look like likely leprosy cases to Dr Jacques. It’s an approach that respects and works with the local culture, not against it.

I generally don’t hand out any money when I work. For a start I’m usually photographing people who are being encouraged by an organisation to find sustainable solutions for living. You don’t want people to rely on the next white man to provide their food. Also if I gave out money to everyone I felt really needed it, I wouldn’t be able to fund half of these projects (the self-funded half naturally). I’m hoping I can be more useful in an indirect, long-term role.

However this next lady really moved me into giving the pathetic 3800 Congolese francs (around four US dollars) I had in my pocket.

It’s not that Tapita Pugbale has a particularly sad story. Granted, her husband died in the late nineties, but that is hardly unusual, and in this culture it seems, barely worth mentioning. She lives in one of the huts built from a collaboration between ALM and Habitat for Humanity.

And ALM loans her the aforementioned soap, coffee etc to sell to make a living. She is not particularly good at it – she is unable to walk to market, so sells it from in front of her hut, hardly the busiest place in Gemena.

She’s wearing a clean white top that Jacques gave her as a present (she is genuinely pleased and excited to see him when we arrive), and wandering into her hut sunlit through thin orange sheets, she has the expected curiosities on the wall… I wonder how often her tie collection gets put to use? Or perhaps it’s a part of her husband she won’t let go of.

She is unable to pound cassava or do much of the house-labour women here are brought up to do the moment they can be pulled out of school (on the occasion they ever went to school). She still has reactions to the bacteria inside her, even though it is now dead and she is no longer considered (at least by definition courtesy of the World Health Organisation) a leprosy-sufferer. In fact I’ve seen many many cases like hers. From a Leprosy Mission’s standpoint she is an average elderly woman who still carries a few marks of leprosy. Better than average perhaps, as she has suffered no stigma throughout her time, and her church group has come to pray with her when she has been unable to walk to the Sunday service.

But she still struggles to make a living. She has rarely been able to repay the loan from ALM that Dr Jacques has provided. But he says she doesn’t spend it wildly… aside from once spending it on a grandsons funeral she spends it on food for herself. She has no family around to look after her, and when I visited she was lying on her bed, weak, having only eaten a small bowl of cassava leaves that morning. She was hungry, and clearly life’s lot has made her weary and very emotional. She started crying mid-sentence and said, “I’m hungry, but what reason do I have to live? I just wish my husband could come back and take me to heaven with him.”

There’s not much you can say to that. I looked at Jacques and said I’d like to give her these francs. He nodded, his face still and solemn, despite being used to hearing these things everyday since he started his job. “Yes, that would be good”.

When I left Tapita’s, Jacques turned to me and said “you know, without ALM Tapita really would be dead. We provide the medication she needs from the reactions to the dead bacteria. If she wasn’t so close to where I live she would have died a long time ago”.

I read an article recently called “Hiding the Real Africa“; about NGO’s faking facts and figures to make the need seem greater than it really is in order to get donations flowing in and to sustain their organisation/business. But I haven’t sensationalised anything in this post. The DRC has a long way to go to bringing it’s people towards the standard of living reflective of it’s natural wealth. Probably far beyond my life time. I hope not. But at the moment it’s the efforts and encouragement from ALM and the likes of Dr Jacques that are what gives thousands of people affected by leprosy a chance. People like Tapita cannot afford to wait for their government to play catch-up with the rest of the world.